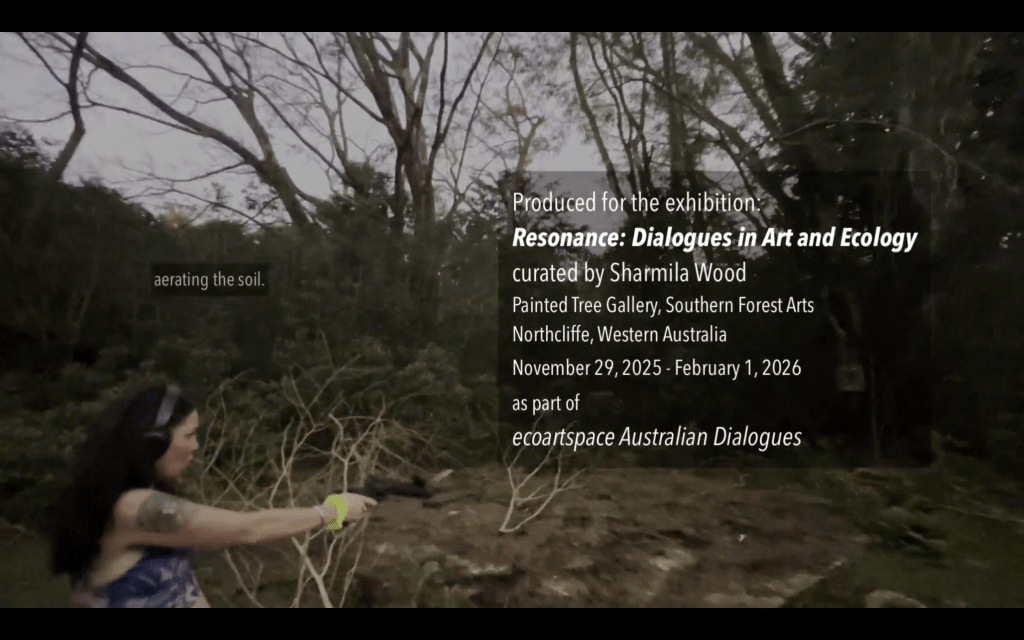

Trans-planted Signals: Navigating Sensory Relationships with Plants, Place, and Pathways

WhiteFeather Hunter

With contributing video by Kate Goff (Western Australia) and Georgie Hunter (Hawai‘i)

Trans-planted Signals is an ongoing research-creation video work that investigates relationships between plants, place, and pathways of adaptation across hemispheres: filmed in Maui, Hawai‘i and around Boorloo (Perth), Western Australia, the project traces resonances between two coastal ecologies that share a long, complex history of botanical transposition through migration and colonization across the Pacific Ocean.

Through gestures of embodied observation and personal memory recall, the work explores how transplanted species and humans who live alongside them, have formed new relations within unfamiliar terrain. The project considers orders of belonging, displacement, colonial imprints, and ecological kinship, by examining how sensory and material attunement bridges distance between homes, histories, and hemispheres.

Research Context & Methodology

Rooted in eco-art sensibilities, Trans-planted Signals approaches plants as living archives of cultural migration. The primary focus is on Australian species that have become naturalized or invasive in Hawai‘i (starting with Australian pine, Norfolk pine, Hau, and Paperbark), attending to how their transplantation has altered ecologies and sometimes become interwoven with cultural identity (and tourism).

Methodologically, the project employs a situated, sensory echo of fieldwork: listening and knowing through place, memory, and embodied presence rather than aloof observation. It translates autoethnographic experience into moving image and voice, where gestures of walking, cycling, and tending become research and performance.

The work deliberately adopts a naïve tone in its narration (and subtitles), as an intentional strategy to make complex or contested issues such as colonized ecologies, cultural belonging, and displacement accessible through the language of wonder and self-reflection rather than externalized authority. This approach softens didactic distance, allowing viewers to enter the work through a more personal lens before engaging with its punchier political concepts.

Process & Production

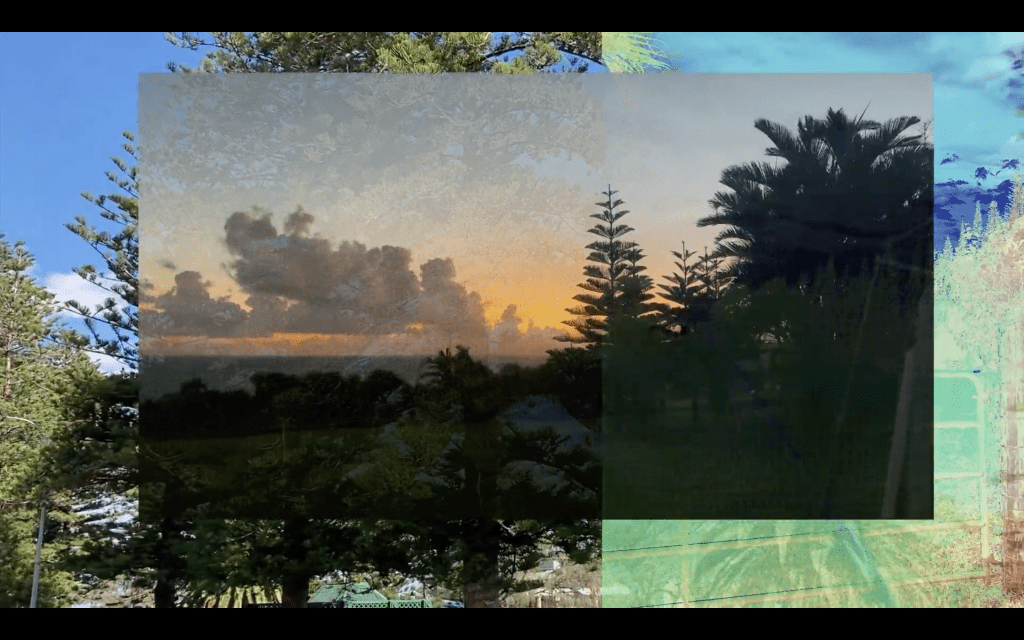

Filmed between 2019 and 2025, Trans-planted Signals uses botanical long shots with shoreline sequences, and first-person narration to create a field of dialogue. The camera becomes a sensing instrument, interlacing footage captured in both hemispheres to generate a sense of spatial and temporal disorientation. Multiple overlapping videos are juxtaposed (some colour-inverted) to make disparate locations less distinguishable from one another, with moments on Maui creeping into Perth, coastlines and light signatures fading into one another.

This visual confusion is an aesthetic strategy to echo the intertwined histories of place (also invoking Maui’s history of plantation fields) and to evoke the perceptual dislocation that accompanies migration of both plants and people. The simultaneity of image gestures toward ecological identity as always in motion.

Narrative Fragments from the Field

I discovered this tree by sound before I knew what it looked like.

It had a whispering hush, rare in the noises that typically permeate the air in Perth.I was compelled. I was drawn to it. And then I discovered that horses were drawn to it, too. They like to chew on it to quench their thirst. I learned that its thirst-quenching properties were discovered by Indigenous Australians.

These trees have an affinity for salt water, living by the ocean, loving the pure ocean air, just like people, dancing in the wind, hanging out at the beach. I’m not Indigenous to either one of these places. But there’s nowhere I feel more at home than next to the ocean. The Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean. Really, though, I’m from the Atlantic.

I cycled hundreds of kilometres in Perth, and sometimes the Norfolk pines were the only thing that gave me shade.

My auntie planted these Norfolks all in a row forty-some years ago; they line the driveway that goes down the gulch where the dragon fruit trees grow. Every Christmas, my dad cuts down the top of a Norfolk pine. They grow so fast, they need to be cut back and every year, it becomes my Christmas tree. There’s a really tall one near the house where I stay, and the roots are starting to clog the septic system. That way, everybody has to give a shit about this tree. On the farm, on Maui, the myna birds sit in the very top of this tree, waking me up every morning.

But in Perth, at Cottesloe, I used to love going to the beach at sunset just to listen to the lorikeets fly in, all singing together, making so much noise you couldn’t even hear yourself think. Sometimes that’s a good thing.

Where I lived in Crawley, there was a hedge out front, and at first I didn’t recognize it. Then it slowly dawned on me: this is hau bush! I didn’t recognize it because in Maui, the hau bush grows out of control, a tangle, deep jungle, impenetrable. But in Perth? It was just decorative. It was tame. It stayed within the boundaries of its box, providing little yellow flowers that turn red at sunset and fall off.

On the farm, my stepmother showed me that hau bush was one of the canoe plants the early Polynesians brought to the islands. Its bark can be stripped into long, thin fibres to make rope or weave baskets.

I didn’t know much about Paperbark, other than that it punctuates the landscape around Perth and Fremantle. But in Maui, I learned that it’s highly invasive. It takes over the native species that Hawaiians use to make pounded fibre cloth.

Wild boar have taken over the ranch, digging the ground, favouring plant species that are invasive: Ink berry. They dig up gardens, they root through the earth, aerating the soil.

Is it good, or is it bad? They provide food for families. One needs to know how to shoot a gun.

How far will we go to preserve the plant species we most identify with?

Epilogue

Dr. WhiteFeather Hunter has lived and worked on Maui, on her family farm and ranch periodically since 1989. She lived in Perth for five years between 2019 and 2024 while completing a PhD at The University of Western Australia.

Trans-planted Signals arose from her desire to understand the many Australian plant species that have naturalized or become invasive in the Hawaiian Islands, and how these botanical migrations have become deeply woven into cultural identity. The project reflects both personal geography and broader ecological narrative: a life lived across oceans, tracing kinship through the shared movement of trees.

Credits & Acknowledgements

- Year: 2025

- Medium: Multi-layered single-channel video with sound

- Concept, direction, primary video, and editing: WhiteFeather Hunter

- Contributing video: Kate Goff (Western Australia); Georgie Hunter (Hawai‘i)

- Sound: WhiteFeather Hunter (narration), in situ car radio snippets of the Hawaii 5-O theme song (1968) recorded in situ at Peahi (Jaws), Maui; modified snippet of Mele Kalikimaka sung by Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters (1950).

- Filming locations: On the unceded lands of the Kānaka Maoli (Hawai‘i) and the Whadjuk Noongar people (Australia)

With gratitude to the transplanted species and the lands that hosted this work—teachers of endurance, adaptation, and reciprocity across oceans.